MASTER CLASSES

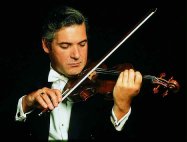

Pinchas Zukerman masterclass. Sydney, Australia. August 31, 2000: - Renowned violinist/violist Pinchas Zukerman, visiting Australia as part

of the 2000 Olympics Arts Festival, presented masterclasses in three

cities. Students from around the country auditioned by tape for the

chance to participate and four were chosen to perform at each class.

In Sydney, the students were all violinists; most were prize winners of

local and international competitions with impressive resumes and all

were about 18 years old and currently undertaking tertiary training. Of

course, violin and viola students and teachers came from near and far to

watch, learn and take the rare opportunity to ask questions of the

master. Pinchas Zukerman masterclass. Sydney, Australia. August 31, 2000: - Renowned violinist/violist Pinchas Zukerman, visiting Australia as part

of the 2000 Olympics Arts Festival, presented masterclasses in three

cities. Students from around the country auditioned by tape for the

chance to participate and four were chosen to perform at each class.

In Sydney, the students were all violinists; most were prize winners of

local and international competitions with impressive resumes and all

were about 18 years old and currently undertaking tertiary training. Of

course, violin and viola students and teachers came from near and far to

watch, learn and take the rare opportunity to ask questions of the

master.

Violinist, violist and conductor Pinchas Zukerman was born in Tel Aviv in

1948. He began his musical studies with his father, first on recorder and

clarinet and later on the violin. At 8, he entered the Israel Conservatory

and Academy of Music, studying with Ilona Feher and in 1961, with support

from cellist Pablo Casals, went to the United States to work with renowned

pedagogue Ivan Galamian at the Julliard School. Zukerman won the prestigious

Leventritt Foundation International Competition in 1967, which launched his

stellar career as one of the world's finest violinists. He is also well-known

as a chamber musician, performing on both violin and viola with colleages

including Itzhak Perlman, Isaac Stern, Daniel Barenboim, Vladimir Ashkenazy,

the Tokyo String Quartet and the late Jacqueline Du Pre. As a conductor, he

has worked regularly with the St Paul Chamber Orchestra, the Dallas Symphony

Orchestra and the English Chamber Orchestra. In 1998, he was appointed as

musical director of the National Arts Orchestra of Canada. Zukerman, who

records exclusively for BMG Classics/RCA Victor, has an extensive discography

which has earned him 21 Grammy nominations and two awards. Biography written by © Lee Anthony Violinist, violist and conductor Pinchas Zukerman was born in Tel Aviv in

1948. He began his musical studies with his father, first on recorder and

clarinet and later on the violin. At 8, he entered the Israel Conservatory

and Academy of Music, studying with Ilona Feher and in 1961, with support

from cellist Pablo Casals, went to the United States to work with renowned

pedagogue Ivan Galamian at the Julliard School. Zukerman won the prestigious

Leventritt Foundation International Competition in 1967, which launched his

stellar career as one of the world's finest violinists. He is also well-known

as a chamber musician, performing on both violin and viola with colleages

including Itzhak Perlman, Isaac Stern, Daniel Barenboim, Vladimir Ashkenazy,

the Tokyo String Quartet and the late Jacqueline Du Pre. As a conductor, he

has worked regularly with the St Paul Chamber Orchestra, the Dallas Symphony

Orchestra and the English Chamber Orchestra. In 1998, he was appointed as

musical director of the National Arts Orchestra of Canada. Zukerman, who

records exclusively for BMG Classics/RCA Victor, has an extensive discography

which has earned him 21 Grammy nominations and two awards. Biography written by © Lee Anthony

Suggested Etiquette Suggested Etiquette

|

Violin

Violin sheilascorner Home

sheilascorner Home Photography

Photography Websites

Websites Contributed and written by ©

Contributed and written by ©